Published March 18, 2021

Updated January 25, 2022

Originality and Ownership in Digital Art

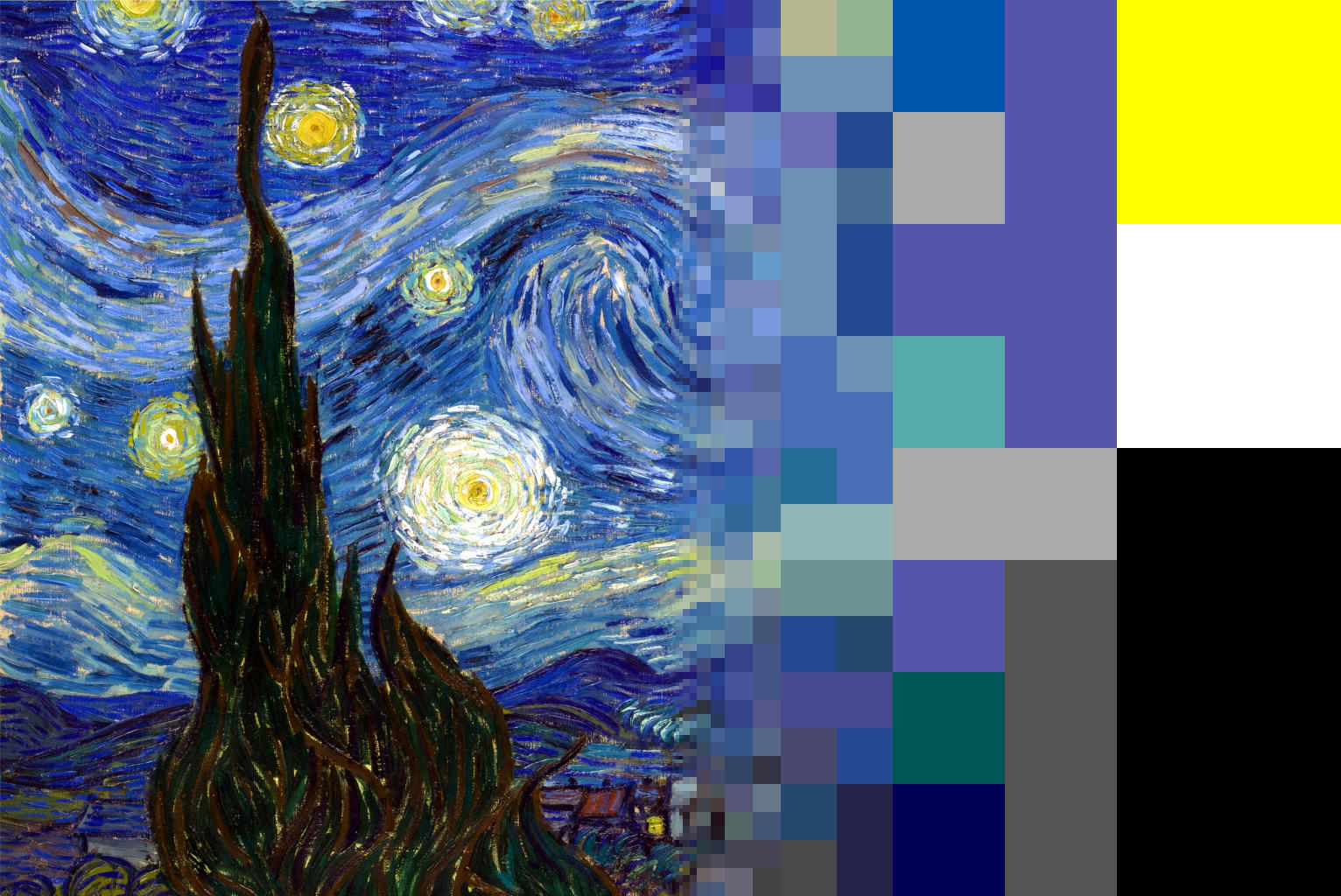

(Quantized Starry Night, source image from puzzlewarehouse.com, edited by Pavel Soukenik)

The idea of owning an original digital art can be both intriguing and confusing. How do the concepts of originality and ownership transfer from physical to digital art? And are some historical works of art digital in nature?

Crypto art has been making headlines over the past several months with reports of pieces of digital art fetching record-breaking sums in auctions. After each major transaction, there have been articles both questioning and defending the legitimacy and value of crypto art.

Buying and trading crypto art is often compared to that of physical art. This is for good reasons, but it is also important to be aware of their inherent differences.

Analog and Digital Worlds #

The words analog and digital are so ubiquitous that they became somewhat divorced from their meanings. In this context, ‘analog’ means continuous (literally ‘proportionate’), and ‘digital’ means discrete (‘numerical’).

We live in an analog world. Our senses perceive signals that are inherently continuous — both in how they change over time and in their intensity. These real world, analog signals can be converted into a series of quantized discrete measurements1 and stored as a sequence of numbers. This digital representation can be stored and converted back into an analog form, so we can hear or see what was recorded.

Let’s set aside questions about the process and accuracy of the conversions, and focus on the differences of these two forms in the context of art.

Pros and Cons #

Analog and digital works of art have their own advantages and disadvantages.

Physical art is subject to deterioration but has a unique form. A marble statue is going to deteriorate much slower than a printed photograph, but the second law of thermodynamics affects both. And while some items (like photographs) are easier to reproduce, it is impossible to fully duplicate a physical object.

On the other hand, digital art is data. The number 15,078 is a piece of information. It will never change. As long as we preserve the data of a digital object, it is immune to deterioration. And if you store my number 15,078 on your computer, you have the exact same piece of information.

Depending on your philosophy or needs, these characteristics can be good or bad. If you want to preserve a film print of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: Space Odyssey, the impermanence of analog is your enemy. If you are selling songs on the internet, you contend with the ease of creating copies of digital files.

Originality #

What does it mean when a piece of art is an original? And is it different in analog and digital?

“Original” art is usually defined as something created directly by the artist and being the first of its kind. The definitions aim to specifically exclude copies. But even in an analog world, the interpretation can be a bit fluid. If a photographer makes 200 prints of a photograph, are they all originals?

In the digital realm, the concept of originality is even trickier. Is my number 15,078 original? If so, which instance is the original? The one that went briefly through my computer’s memory as a sequence of characters I typed, or the first copy saved in my local GitHub repository? Trying to pin down something in relation to digital information is a fool’s errand.

Books As Digital Doubles #

To help think about this topic, let’s consider books. Yes, we can look at books primarily as physical artifacts, and many collectors do. A rare first edition is a part of an original set, just like the 200 photograph prints. But we can also think of a book as information.

In this sense, two printed editions and an ebook with the same words in them are the same book. If I own any of the three, I have the book. In contrast, a statue is a unique physical object. Maybe I could get its digital model and 3D print it, but it would be different than the original. I would not have the statue.

Seen this way, books — but also Beethoven’s symphonies — are composed of discrete pieces of information. Both are digital in nature, even though they also have physical representations. These ‘analog conversions’ add their own beauty to their renditions of the analog forms, but at their heart, books and symphonies are not analog.

Digital Is Not Worthless #

Digital art is just like a book in its abstract form. It is pure data. It does get reproduced into an analog representation for consumption, but the underlying data of each digital copy are identical.

Do I think that an animated GIF is as important a work of art as the Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5? Of course not, but it is noteworthy that in a very real sense, they are both digital works of art.

(Intellectual) Ownership #

I would argue that information — whether it is contents of a book or a digital file — can only be described as an original when speaking in an intellectual sense: as the act of first thinking of something and committing it into a form that is shared with others is noteworthy.

The concepts of intellectual property rights, licensing, and ownership have developed as social norms for crediting and rewarding artists precisely because some works can be easily copied or duplicated to a point that smudges (or eliminates) the difference between an original and a copy.

Crypto Art #

What makes crypto art2 different from other digital files is that they are associated with sophisticated blockchain records using a “non-fungible token” (NFT). Blockchain is a robust method to document and prove all transactions related to the tokens. Since the artwork and token both exist digitally, the token cannot be physically reattached to a different work of art.

Interestingly, NFTs do not focus on (or address) the problem of validating or proving the ownership of intellectual property.

Ownership in NFT #

What legal rights (if any) are being exchanged with the sale of the token depends on each situation. Most often, the only right granted by the author is a license for use. In many cases, the exact same digital content is also available publicly without the NFT.

Articles talking about NFT often talk about acquiring ownership. They sometimes fail to clarify ownership of what. In a made up example, imagine Queen auctioned off NFT to their Innuendo album as originally released on CD. If someone paid a few millions of dollars for it, what would they own?

It would not be the intellectual property rights or exclusive rights to use. The associated work of art would be identical, bit for bit, with the CD at a regular price. The ownership would be of a public record of having payed for the NFT associated with that digital album.

Could then Queen auction off separately the song The Show Must Go On from that album? Technically, yes. Could you go and create an NFT for someone else’s song? Troublingly, also yes.

The only inherent ownership in crypto art is the ownership of an undisputed record of a specific transaction in relation to that asset.

A Critical View #

In the world of fine art collecting, just like collecting in general, the value of what someone is paying for or trading is not directly linked to the underlying value of what changes hands.

In essence, while the digital art might have its own value, there is no underlying value of the NFT proper because it is a purely virtual token associated with something else.

Trading Receipts #

In his informative and thoughtful article explaining NFT art, Mitchell Clark asks: Why would anyone buy crypto art — let alone spend millions on what’s essentially a link to a JPEG file?

Reading his article, it’s not hard to see NFT as the logical end point when the value in collecting art is divorced from the artwork’s intrinsic value. Aaron Hertzmann expressed it as follows:

If the point of ownership is to be able to say you own the work, why bother with anything but a receipt?

His quote is even more striking given the restricted meaning of the word ‘ownership’ in this context.

Hertzmann does a good job of answering the question “why people buy original works of art.” That sentence is also the only occurrence of the word ‘original’ in his article. The concept is alluded to again later when he writes: “This does not mean that art is interchangeable, or that the historical significance and technical skill of a Rembrandt is imaginary.”

The Monet Conflation #

In an article NFTs explained: what they are, and why they’re suddenly worth millions, Mitchell Clark makes statements that are factually correct but easy to overinterpret:

NFTs are designed to give you something that can’t be copied: ownership of the work (though the artist can still retain the copyright and reproduction rights, just like with physical artwork). To put it in terms of physical art collecting: anyone can buy a Monet print. But only one person can own the original.

“Ownership of the work” is a big phrase for describing ownership of a token. It is also important to realize that thing that “can’t be copied” is the NFT, not the artwork to which it is applied.

As is, the analogy is overstretched. A Monet’s painting is a unique object while the crypto art exists in a multitude of identical instances. The statement conflates the artwork with the token and a receipt for a transaction.

Clark admits later in the same article: “With digital art, a copy is literally as good as the original.” And in digital world, “as good as the original” means “identical.”

If Monet lived today and created his art as digital files available to purchase (like music downloads), it would be more accurate to say: “Anyone can buy an original Monet image. But only one person can own a unique token associated with it.”

Trade with Eyes Open #

Does that mean crypto art does not have value? No. The value people place in collecting things (art included) is largely subjective. The goal of this article was to explore how originals exist in digital world, and what ownership in crypto actually relates to.

The value of crypto art is based on what someone is willing to pay for a unique token associated with something that can exist in a multitude of instances. This clearly sounds good enough to a lot of people.

Coda #

Personally, I am not trading NFTs for three reasons: I love tangible and analog things; I prefer to trade with things that have a corresponding underlying value; and I am very concerned about the environment.

The environmental impact should not be overlooked: Crypto currencies and NFTs are hugely energy hungry. We can live without crypto until this is addressed but we cannot live without functioning ecosystems.

If you still want to go ahead, do it with eyes wide open and donate a sufficient part of your proceeds to carbon offset the environmental impact of your trades.

-

The image at the top of the article illustrates this. From left to right, both the sampling frequency and bit depth for quantizing the RGB channels is reduced by a factor of two with each step. ↩︎

-

The concept was very recent at the time of writing but it still bears clarifying that this article is about digital art only, and not physical works with an attached tag which ties them to a cryptographic record of ownership. ↩︎