Published May 9, 2010

Updated January 29, 2022

Keyboards and Their Remarkable Resistance to Innovation

(Image by Apple)

The typewriter was invented around the same time as the telephone, but while phones have changed beyond all recognition, the keyboards of today look substantially the same as when they first made their entrance.

Why do keyboards still look like those on old typewriters? Let’s review some of the attempts at innovations that happened over time and why they failed to become widely adopted. This might give us some clues about the dynamics at play here.

I grew up just as the computers were becoming ubiquitous, so let me briefly start by sharing how I came to be interested in this topic.

How I Came to Care About Typing #

My Grandmother worked in a sugar factory that stood at the end of my village. Part of the year was always filled with the constant noise of tractors hauling beet from the fields to be transformed into refined sugar cubes that would later be served with tea or coffee in nice porcelain cups.

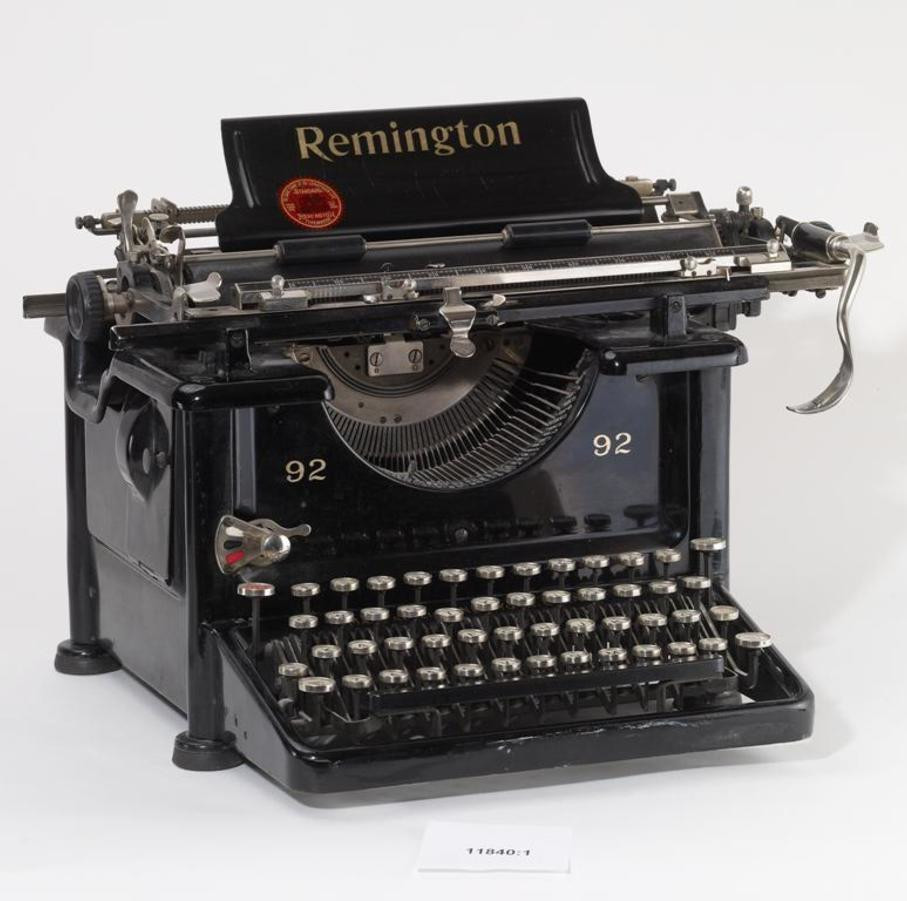

Her office had an electrical typewriter and a phone with a switchboard. There was a lot of plastic and lights. However, at home, in a large wardrobe, below hanging coats and perfumed dresses, she kept an old mechanical typewriter. It was a black metal machine, quite heavy for me to lift and carry to a desk. (Actually, everything seemed sturdier in those days.)

(Image by The National Museum of Finland)

Its keys were beautiful circles with clean lettering and silver rims and quite a long travel; you needed to push those keys with some force be rewarded with a ‘clack’ sound as the letter got printed through an ink ribbon which slowly moved as you typed. I enjoyed replacing the ribbon and setting the typewriter’s bell to ring as the carriage approached the edge of the paper. I typed slowly enough to know beforehand that the next key would produce the bright ring, officially announcing that I could finish the word and push the carriage back—with great satisfaction—using a lever which would also rotate the cylinder to the next line.

The typewriter had a label ‘Remington,’ which looked extraordinarily to a kid growing up speaking Czech. (The intriguing shape of letter “g” appears rarely in Czech). Little did I know that this corporation was partially responsible — besides gun production—for thrusting a questionable standard of the keyboard on the whole world. When I was a kid the words “repetitive stress injuries” did not mean a thing; but that machine was the most intriguing toy I’ve ever had.

Inventors’ Legacy #

One thing that children do very well is asking questions. What is this? What is that? The most interesting questions start with ‘Why.’ I found the key arrangements strange but it didn’t occur to me to seriously ask this question until a bit later: “Why are the letters on the keyboard arranged like this?”

There are many detailed accounts of the history of the typewriter and its keyboard layout, and at least as many myths. The typewriter that came into mainstream use was invented by Christopher Latham Sholes in 1867.

Key Ordering #

Initially, the mechanism that returns the heads of the keys after imprinting the letter on the paper relied on gravity. Sholes initially laid out the keys alphabetically. This led to jamming of neighboring keys, so Sholes experimentally modified his alphabetical layout to separate common letters. And thus came up with what we now accept without much thinking as the standard keyboard layout, the QWERTY.

This change was not done to slow down typists, as is often incorrectly said. There had not been any trained typists back then. While the initial alphabetical idea would have had the benefit of allowing new users to find the keys, from the perspective of the soon-to-arrive era of touch typing, it would largely be irrelevant.

Physical Layout #

Another enduring legacy of the old mechanical days — which rarely enters into conversations about keyboard ergonomics — is the staggered positioning of the rows of keys. This progressive offset from right to left, moving from lower to higher rows, allowed the metal arms of the mechanical typewriters to fit without overlapping. Its only real ‘function’ today is to force our fingers into an unnatural twist. This is more true for the left hand because most of the fingers on the right hand extend more naturally to the left.

Take a moment to imagine if dialing a number on all touchscreen phones consisted of tracing semi-circles on a rotary dial. Phones switched from a dial to buttons even before the move to digital. The fact that even keyboards that label themselves as ergonomic cling to this staggered layout is fascinating.

First Attempt at Improvement #

When the typewriters were upgraded with springs to return the keys faster, Sholes actually wanted to update the so-called QWERTY layout to make it more efficient but the manufacturers were against changing the (barely) established standard. Because the typewriter components would be a bit harder to swap around, and primarily because this would introduce competing layouts between manufacturers, the changes were not adopted.

This reluctance is understandable. Sure, the manufacturers were competitors. But introducing too many different layouts would risk sinking the business for all of them. This same scenario has played out over and over again in different categories. And it’s usual that companies agree to align on one standard (even though they might fiercely compete initially to make sure it is their design that prevails.)

A Challenger #

By the time August Dvorak, professor at the Seattle’s University of Washington, scientifically approached the problem in 1932 and proposed a ‘simplified’ layout with his brother-in-law, the standard had really been established. Dvorak’s Simplified Keyboard was based on the analysis of English language, and took into account how typists learn and the ergonomics of the movements during touch typing.

Although Dvorak’s pupils were achieving faster typing speeds with fewer typos, the biggest argument against the new layout at that time was the cost of converting the physical typewriters and retraining of typists. The fact that the ‘Simplified Keyboard’ was demonstrably easier to learn and faster was insufficient.

Enduring Question: Is It Really Better? #

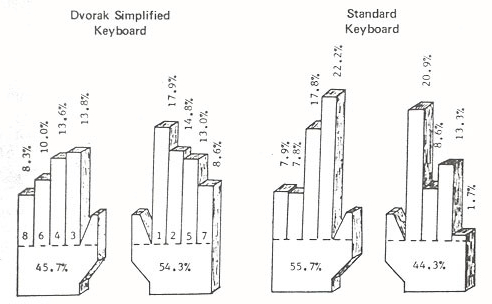

From today’s perspective, Dvorak was putting too much emphasis on speed and efficiency. The fact that today’s fastest typist is using QWERTY is not a testament to its equality, merely a proof of the effect of population size on normal distribution. Trained typists on the Simplified Keyboard created world records for typing speed, and by examining the differences, Simplified Keyboard is inherently a more efficient layout. But, as I’ll point out later, the difference in speed is not a good enough argument to switch.

Where the difference really lies is the amount of finger travel, and therefore increased comfort and decreased strain. If you watch someone type on Dvorak Simplified Keyboard, you’ll notice the lack of movement. From ergonomic perspective, this is a huge deal.

In context, since Dvorak had to convince manufacturers to change physical design of typewriters and make employers invest in retraining thousands of trained typists, increased efficiency was the only argument they would hear. (Ergonomics and preventing injuries were not even on the radar.) Unsurprisingly, despite a lot of effort on Dvorak’s part, his invention has not been adopted.

Legacy #

Dvorak’s Simplified Keyboard has became a favorite example of how a better standard can lose to a worse — but more established — one. Some people argue this is not technically true but only because they take into account a narrow (or misrepresented) part of the benefits of Dvorak’s design.

I continue to be convinced that often very visible hand of the market is responsible for the demise of a fair number of superior alternatives, powerfully supported by a combination of corporations’ appetite for profit and the human reluctance to change.

Should You Learn Dvorak? #

If you can already touch type, you can be very fast on QWERTY. Unless you have health considerations (such as carpal tunnel syndrome), you should likely stay with it. If you type in English and cannot touch type, I recommend learning touch typing using Dvorak. It makes it impossible to fall back on the hunt-and-peck style while learning, and it is an ergonomically superior design. (More details about the comparison of Dvorak and QWERTY is in the appendix at the end of this article.)

Physical Layout Innovations #

Majority of maintain the staggered rows: the ring finger travelling between keys W, S, and X is performing a much more acrobatic journey than the one with an easy commute between O, L, and full stop.

Unfortunately, even many keyboards that label themselves as ‘ergonomic’ do nothing about this. While the vast majority of ‘split’ keyboards offer a more comfortable angle for the arms, they keep the offset on both halves in the same direction. The offset, if anything, should be mirrored, otherwise the left hand is strained. The industry assumes that everyone would rather slavishly bend to a 150-year-old design than to take a few hours to get used to either a straight (ortholinear) layout or one that copies the human hand.

A Better Keyboard #

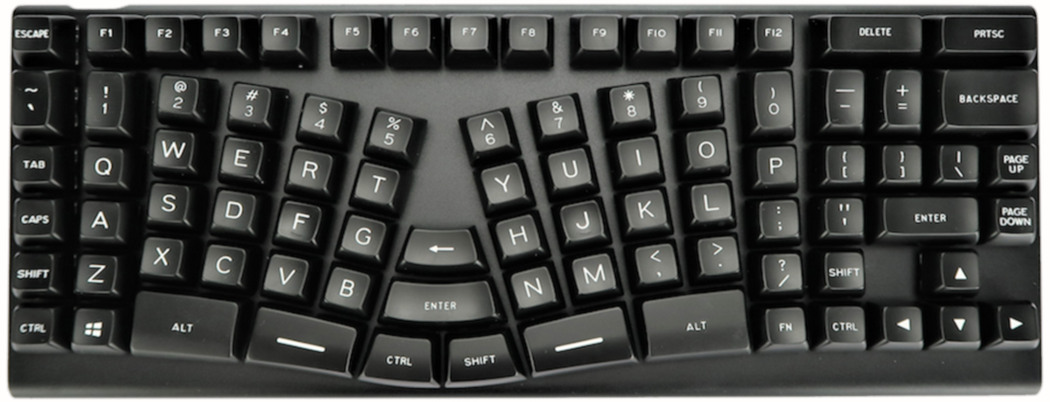

Without going overboard with the design, a mainstream, simple keyboard should have long looked something like this:

Notice the following features:

- The rows are not staggered, but facilitate natural movement of fingers of both hands to reach up and down.

- Enter and Backspace are available in prominent positions, instead of being pasted onto the edge of a 19th century design to serve as stretch goals for the pinkie.

- Caps Lock is smaller and on the fringe, awaiting extinction.

Really ergonomic designs further modify the relative distances of keys between different fingers (taking into account the differences in the length of the fingers), articulate the third dimension to match the natural travel of the fingers, and may adjust the weight required for pressing the keys.

Laptops contend with constrained space so it’s understandable if the two halves of the keyboard are not angled. It is shocking though that as of 2021, there is not a single laptop on the market that would have an ortholinear layout as opposed to the anti-ergonomic staggered layout.

Stenography and Chorded Keyboards #

An alternative method of inputting text which deserves its own article is stenography. Stenography is a very efficient – but much harder to learn – way of entering text because whole words can be formed by simultaneous presses of ‘chords’ of keys.

Stenography typically uses specialized keyboards but there are software emulations for PCs. Exploring this topic eventually led me to an idea of a hybrid keyboard entry which combines chords for frequent words with regular typing.

Looking into the Future #

Christopher Sholes died in 1890; typewriters were on the rise and opening employment opportunities for women. My grandmother’s old typewriter that I first learned to type on was built just before August Dvorak designed the Simplified Keyboard. Dvorak died in 1975 — two years before home computers would allow people to switch keyboard layouts at will. His contribution is now almost forgotten. The use of his keyboard was recently estimated at around two thousand people worldwide.

We are looking at a real possibility that the primary input method is going to transfer from keyboards to voice without the keyboard having evolved much at all in close to 150 years.

I speculate that the fear that people would not want to adapt to a change in something complex like a keyboard combined with the lack of a sustained push from a real innovator is what separates the success of evolution in phone interfaces from the stagnation of keyboards.

Our software products are developed in constant innovation but largely using keyboards that are pre-historic in comparison. The least we should do is demand that manufacturers start building keyboards and laptops with physical layouts that take at least a tiny step toward innovation and ergonomics.

Appendix: Dvorak vs. QWERTY #

Why exactly is Dvorak Simplified Keyboard superior to QWERTY?

- All frequently occurring letters are on the ‘home row.’ (70% of typing happens there vs. 32% on QWERTY.)

- Typing is proportionately distributed between the fingers; and the right hand has a slightly more demanding job.

- Key strokes alternate better between hands.

- The least frequently used keys are on the lower row which is the hardest to hit (Dvorak keyboard uses this row half as often as QWERTY).

The criteria Dr. Dvorak and Dr. Dealey used for the Simplified Keyboard were based on research and investigation with scope that amazed me when I read their book Typewriting Behavior. Yet, despite all its advantages, it is amazing how little used and known the Simplified Keyboard is. It is not even supported by many devices at all: iPhone comes to mind — although, ironically, Apple’s co-founder Steve Wozniak is a Dvorak typist.