Published August 19, 2021

Updated February 13, 2022

Authograph HHH

Interpreting 2001: A Space Odyssey

How Intentional Ambiguity Leads to Richer Interpretations

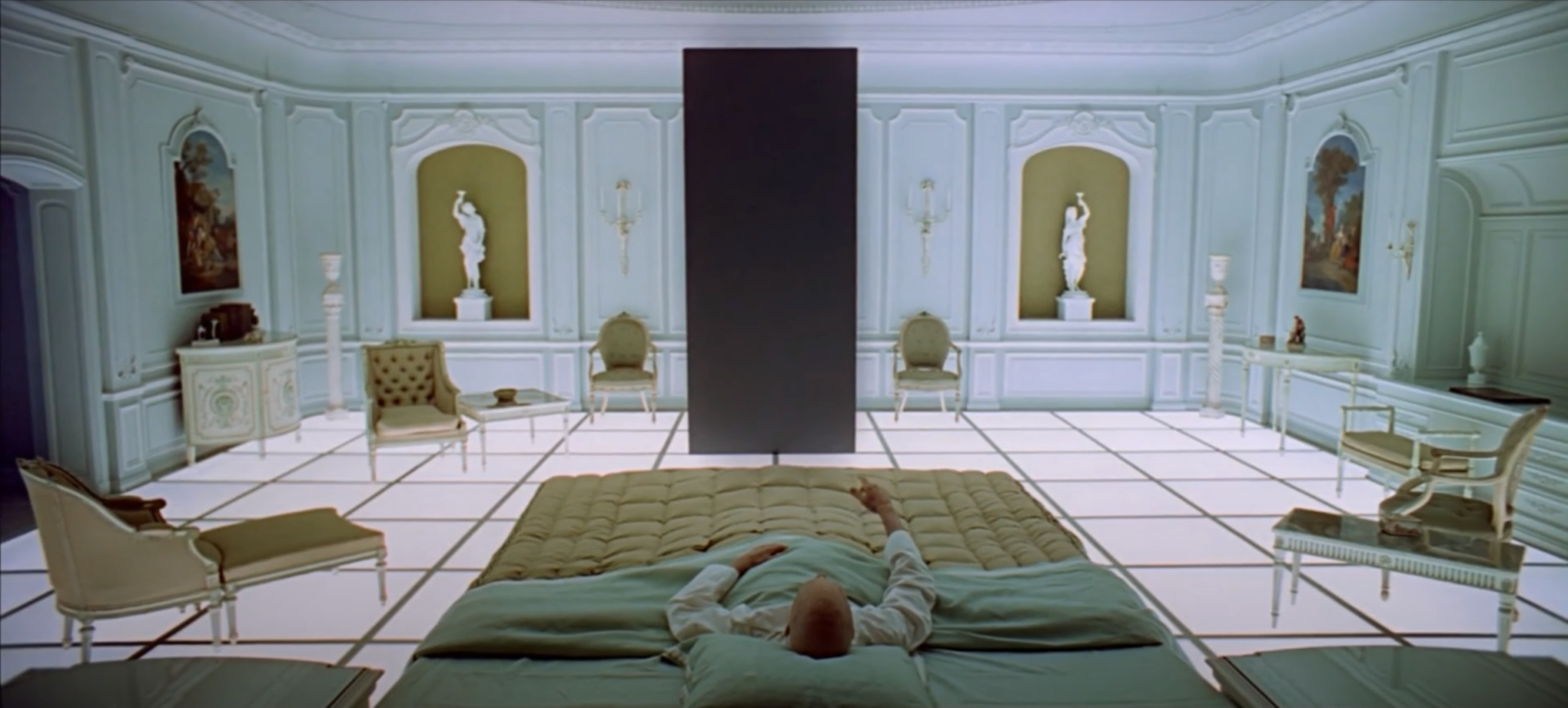

The last scene with the monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey. (Image copyright Warner Bros. Entertainment)

The impenetrable black monolith in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey neatly encapsulates the qualities of the whole film. Its meaning is as opaque as its surface. The ambiguity of its function is the complete opposite of its clearly defined form.

Few directors had their works interpreted by critics and audiences in so many varied ways as Stanley Kubrick. There are two connected reasons why Kubrick’s 2001 provokes so many debates and opinions: The first is that – as we know directly from Kubrick – he made the film’s meaning purposefully ambiguous. The second reason flows from this decision and lies in how we respond when encountering opaqueness or absence of meaning.

Decoding the Meaning #

When it comes to encoding and decoding meaning in film, there is a separation in the roles of the artists and the audience. Once the film is written, filmed, edited, and released, the creative process is complete. The artists step back (or can be ignored if they don’t), and it is the audience’s turn to experience the work and form their own impressions and opinions.

Gaps between the intended meaning and the reading can be satisfying in themselves. In Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, the director had a specific idea about whether the protagonist was human but filmed it in a way that still allowed viewers (and even the actor) to arrive at the opposite interpretation. In Mulholland Drive, David Lynch was explicitly trying to increase the possibilities of reading the film in different ways.

Kubrick understood the value of giving the viewers freedom to arrive at their subjective interpretation, and specifically allowed for ambiguity in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

(Over-)Interpreting Kubrick #

There is a wealth of essays and theories about Kubrick’s films. Kubrick’s exacting approach to work – from obsessive preparations, hands-on involvement in all aspects of the film, the huge number of takes he would sometimes insist on – gave rise to a unique argument that is used to justify some far-fetched theories and, incidentally, allows people to treat Kubrick’s works in a similarly obsessive way.

This argument goes like this: “Kubrick didn’t do anything accidentally. Every element of the movie was specifically intended to be that way so it would fit into a grand, hidden puzzle.”

This reasoning would be silly for analyzing a movie by any other director, but for Kubrick? When one article argues that a discontinuity in the position of a dining table was not to achieve a desired framing but mirror a rook move in Dave’s chess game, it’s harder to dismiss. (What critic would want to risk being ridiculed with the words, “I think you missed it, Dave?”)

Apparent mistakes or shortcuts are also debated: Was the use of mirrored sky backgrounds in “The Dawn of Man” sequence meant to signify anything? I do not think so, but it is hard to be certain because we are talking about Stanley Kubrick.

What we do know is that some key elements of 2001 could not have been premeditated. Take the moment when Dave knocks over the wine glass. This idea came from the actor, Keir Dullea. It had not been a part of Kubrick’s plan. This does not take away from Kubrick’s creative genius. He made decisions to include or reject this and many other suggestions as the film was being made. But I believe it shows that many potential readings arise only with the making of the film, and were not originally (or ever) guiding its creation.

Apophenia and Beyond #

Some of the complex 2001 theories are certainly examples of apophenia – seeing meaningful connections in places where they do not exist. Out brains always look for patterns and try to assign meanings to patterns. But sometimes we perceive a pattern (and over-interpret a meaning behind it) even where there isn’t one.

The way an interpretation is presented may range from interesting to problematic. It can be interesting if it points out that you can read the film a certain way, and problematic if it insists that a specific meaning was intended. In art, drawing even erroneous connections can add to the value, as long as we are aware that what we are constructing is not necessarily real.

The underlying reason there are so many theories and interpretations of the meaning of 2001 and the monolith is because Kubrick purposefully did not include explanations for them.

Opaque by Design #

Kubrick preferred not to discuss how to understand 2001 on a higher, philosophical and metaphysical level, because it was subjective and would differ from viewer to viewer. The following statements by Stanley Kubrick are telling:

In this sense, the film becomes anything the viewer sees in it.

I think that 2001, like music, succeeds in short-circuiting the rigid surface cultural blocks that shackle our consciousness to narrowly limited areas of experience and is able to cut directly through to areas of emotional comprehension.

There are certain areas of feeling and reality – or unreality or innermost yearning, whatever you want to call it – which are notably inaccessible to words.

These observation that there are realities and experiences that cannot be described in words and that comprehension can be gained by cutting through our thinking patterns would not be out of place in a Zen fascicle.1

They confirm Kubrick made the film opaque on purpose. The opaque appearance and function of the monolith, as well as the concluding parts of the film – Dave’s travel through the star gate, the sequence in the white room, and the star child – all elude direct reading of what we see on screen and therefore invite us to form our own intuitive interpretations.

The Monolith in the Room #

Nothing in this film is so central to the story and as opaque as the monolith. Even though it does not take up much screen time and it acts in indirect ways, all the events in the film are related to it. The significance of the monolith is established early on with an astonishing economy and without a word spoken.

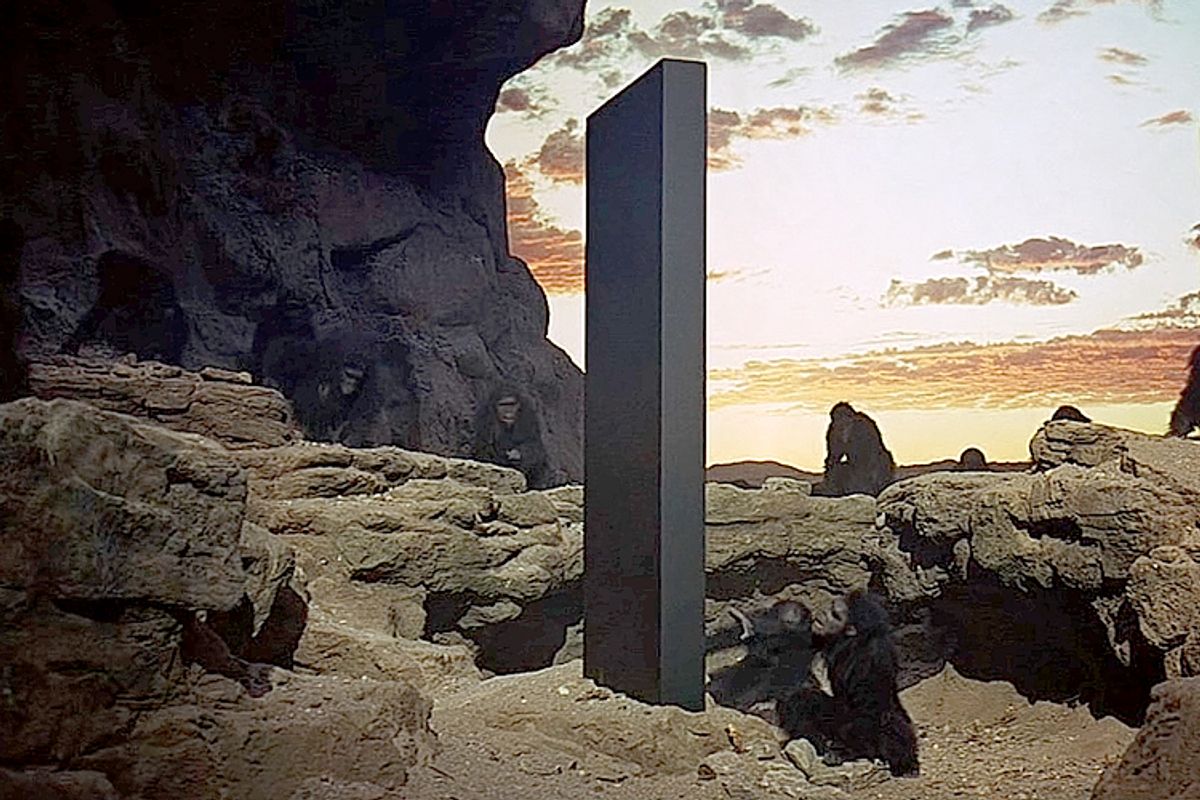

Kubrick first takes us to “The Dawn of Man” and shows us a connection between an encounter with a mysterious monolith and the discovery of tools (and their immediate application as weapons) and then – with a single famous match cut into his audience’s future – links the monolith to all our progress since, just as the monolith is about to alter mankind’s trajectory again.

It is in this second part of the film dealing with the discovery of a monolith on the Moon that we find out the artifact would baffle future scientists as much as it did our ancestors millions of years ago. Where it came from, how it works, and what its purpose is, the film does not say. On the contrary, it explicitly informs us that these facts are a mystery.

The monolith is nowhere to be seen in the next – and longest – part of the film, but its shadow looms large: The whole mission to Jupiter and its events are directly linked to the humankind’s second encounter with the monolith.

The monolith then appears two more times. Without attempting to interpret the events on a higher level, it seems to act as a gate that transports the sole surviving mission member, Dave, through space to a place where he passes the time until the monolith appears to him once more at his deathbed, just before we see him reborn and returned to Earth.

Now You See It, Now You Don’t #

Interestingly, the original monolith was transparent. It was created from plexiglass, using a recently developed technology, at a great cost, but Kubrick rejected it. It was a lucky coincidence, or a very clever reversal of his decision, to make the monolith opaque. In the film, the monolith is opaque not only in appearance but also in its function.

Kubrick originally also intended to show the aliens who created the monolith. After realizing the impossibility of portraying aliens as both completely unfamiliar and recognizable, he told his wife: “The monolith leaves that open void that we feel when we try to imagine that which is unimaginable.”

While in the story, it does send a signal, we don’t see it actively doing anything. Compared to the book written by Clarke in parallel, Kubrick downplays the ‘doings’ of the monolith. The monoliths seen in the film are more passive and mysterious than those in the book. In the film, it turns our attention inward.

Function in the Story #

On a basic level, its function in the story is clear: it appears at key moments of man’s progress and seems to advance, direct, or transform the human race.

In all instances where the monolith appears, some sort of a transcendence is achieved. In the prehistoric portion, it is the discovery of tools that can account for all the progress until the main events of the film. On the Moon, it’s appearance prompts the mankind to take a leap from the Earth and its satellite farther into the Solar system. And in the last sequence, the monolith is the means by which Dave transcends – either in his perspective or on a more literal level – his existence.

Meditative Parallels #

Kubrick has offered us a monolith pointing at Jupiter and beyond, not unlike ‘a finger pointing at the moon’ of Zen writings. Neither can adequately directly describe what they are trying to point to precisely because, as Kubrick himself observed: “Words are a terrible straitjacket.”

The Monolith as a Koan, … #

As part of their practice, many Buddhist traditions use anecdotes, sayings, or riddles – called koans – that go against ordinary reasoning or interpretation. They are purposefully opaque. They are somewhat curious and certainly inscrutable. In all these qualities, they are very much like the monolith. Their real goal is to short circuit the practitioners’ usual way of thinking and to jolt them into a more enlightened, transcendent state.

…, a Mantra, … #

A mantra in the sense of a word or a sound that is either recited or meditated upon, also shares some qualities with koans (and the monolith). Mantras are often purposefully meaningless words. Even if a mantra has an associated meaning, the repetition of a word or a short phrase – out loud, silently, or just by thinking them – strips it of its meaning. As with the monolith, there is nothing to uncover, nothing to ‘see’ beyond the sound. As the mind focuses on the repetition of the mantra, the mantra disappears.

The effect is not dissimilar to the Troxler effect illustrated here. The above image disappears when you look at it without moving your eyes for thirty seconds.

… or Breath #

In 2001: A Space Odyssey, the sound of breathing is prominent through pivotal parts of the film. Some meditation techniques use breath as an object of focus. Whether we pay attention to it or not, breathing is always there. We can consciously control it or let it happen on its own, but it is present as long as we live.

Obviously, there are differences between all these. The breath and the monolith have a concrete physical presence. The optical illusion disappears in our mind while not disappearing literally. A koan or a silent mantra can fade from our consciousness and completely disappear for a time. On the other hand, the monolith is unchanging, opaque, and uniform. But if we look at it up close, it does disappear.

Intuitive Interpretations #

Did Kubrick intend for the monolith to be interpreted the way I did? No, I do not believe he did. At the same time, he would likely not be unhappy with such an interpretation. Kubrick explained that the movie was “a visual, nonverbal experience. It avoids intellectual verbalization and reaches the viewer’s subconscious in a way that is essentially poetic and philosophic. The film thus becomes a subjective experience which hits the viewer at an inner level of consciousness, just as music does, or painting.”

The beauty of art is that the readers and viewers get to interpret it themselves. Had the final film turned out differently, people would have produced different interpretations of its meaning. That is not to disprove or discount any of the existing analyses but rather to reinforce that we should not search for one correct, hidden answer to the meaning of 2001. With this in mind, we are free to enjoy the film and form our own intuitive understandings.

The quotes in the article are from the books The Film Director as Superstar by Joseph Gelmis and Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke, and the Making of a Masterpiece by Michael Benson, and from William Kloman’s article “In 2001, Will Love Be a Seven-Letter Word?” (The New York Times, April 14, 1968)

-

Kubrick was not a Buddhist so this observation in itself is either another example of the human need and ability to seek and draw connections where they do not exist, or an example of a shared wisdom discovered independently by different people. ↩︎